The time I moved out of my school, the image I had of mathematics was of something that you practice a lot to get good scores out of, you remember the “theorems” you see how they are derived if you want that extra edge, it was never something that could help solve real-world problems. I remember making arguments like where am I going to use these matrix multiplications in the real world? Why is it even part of the curriculum? And Today Ironically my job(machine learning engineer) actually requires only linear transforms, essentially matrix multiplications in every architecture I have ever designed. So much for irony! Nonetheless, the idea we are going to explore in this series of implementations is to try and create basic examples from real-life implementation that make interesting use of the phenomena we are familiar with and eventually build enough understanding to explore more complicated things to get the best outcomes for real-life implementations.

The game of tricks

I remember in college fest burning a significant amount of money, on this game. The rules were pretty straight forward, at the beginning of each session, each player will bet a certain amount (in continuation with the mathematics rule we will call it x :P ) the dealer will show you a coin, which is going to be placed underneath one of the three cups. Once the coin is in the place he will shuffle the three cups and the players who have placed bets on these are going to try and guess at the end of each shuffle the cup with the coin underneath. The winner gets 2 times the amount and the loser will lose the entire invested amount, sounds fair enough?

A video demonstrating the same is as follows:

The real trick

The dealer is almost always a trained professional with vast experience of trying to make the tracking look easy when actually it is designed to create an illusion, that creates a bias in favor of a wrong choice. It can also be an outright bluff to reintroduce the coin into a different cup through some neat tricks. Either way, the chances of you winning the bet are not really high. Let’s look at the problem through a mathematical prism.

Here comes the math

Let the amount invested by each player be x. The probability of an unbiased observation will be 1/3

In order to get a good hands-on, the possible outcomes let us create a simulation demonstrating the same. We will run 10 games per player and have 400 such players play and observe how the outcomes look like. The GIF below demonstrates the result of such a simulation, as you can see most of the players end up losing money, this number will increase as we increase the number of games played by each player. The simulation shows:

- Total amount won

- Total amount lost

- Net Profit or Loss

You can access the code that created these simulations here

You can access the code that created these simulations here

So what can we do ?

Well maths to the rescue, what if I tell you that you can always ensure you walk away with a profit from this game?. Crazy right??. Not so much.

Let’s look at the problem in a really different way. What if we get rid of the biases and do a completely random selection? that way we can have an absolute probability equal to 1/3.

Secondly, we are going to introduce a rule for ourselves, rather than making random contributions we are going to invest the sum in a multiple of 2’s.

So for example, if x is the amount invested in the first game, we will invest 2x if we lose and stop playing immediately after we win.

This will ensure that we are always going home with a sum more than we have initially invested.

Let’s look at the maths proving the same.

For simplicity let us assume that the initial amount invested is 1. Meaning x = 1

Therefore owing to our doubling strategy in case we lose the next amount is 2, the next amount will be 4, and so on.

Essentially

1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 ….. [ ]

]

Where n is the number of games that we won. Now doesn’t this looks like something we all know and have read about in the past? Remember GP(Geometric progressions?), well we have at our hand a geometric progression.

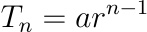

With 1 being the first term and 2 being the common ratio and [ ] being the last term that we have won.

] being the last term that we have won.

Since the progression is a GP we can easily quantify the losses we are going to make, by definition we know that we are losing money until the term (n - 1) or .

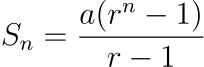

From the definition, we also know that sum of a GP with n terms is

Where a is the first term r is the common ratio, in our case we have been losing money until (n-1)th term

a = 1 r = 2

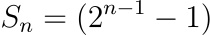

The equation effectively reduces to for n-1 terms as

Now we also know that nth term (last term that is going to make us money)

Putting in values for a and r

Net value = Profit-from-last-term - sum(all-previous-losses)

An interesting observation in this is that the final value is independent of n, meaning no matter how many games we lose money for the final outcome will always be profitable.

Now mathematics is not cramming formulas to be able to solve some quant questions, it’s about solving real-life problems in a logical and comprehensive manner. Stay tuned for more interesting implementations like these.